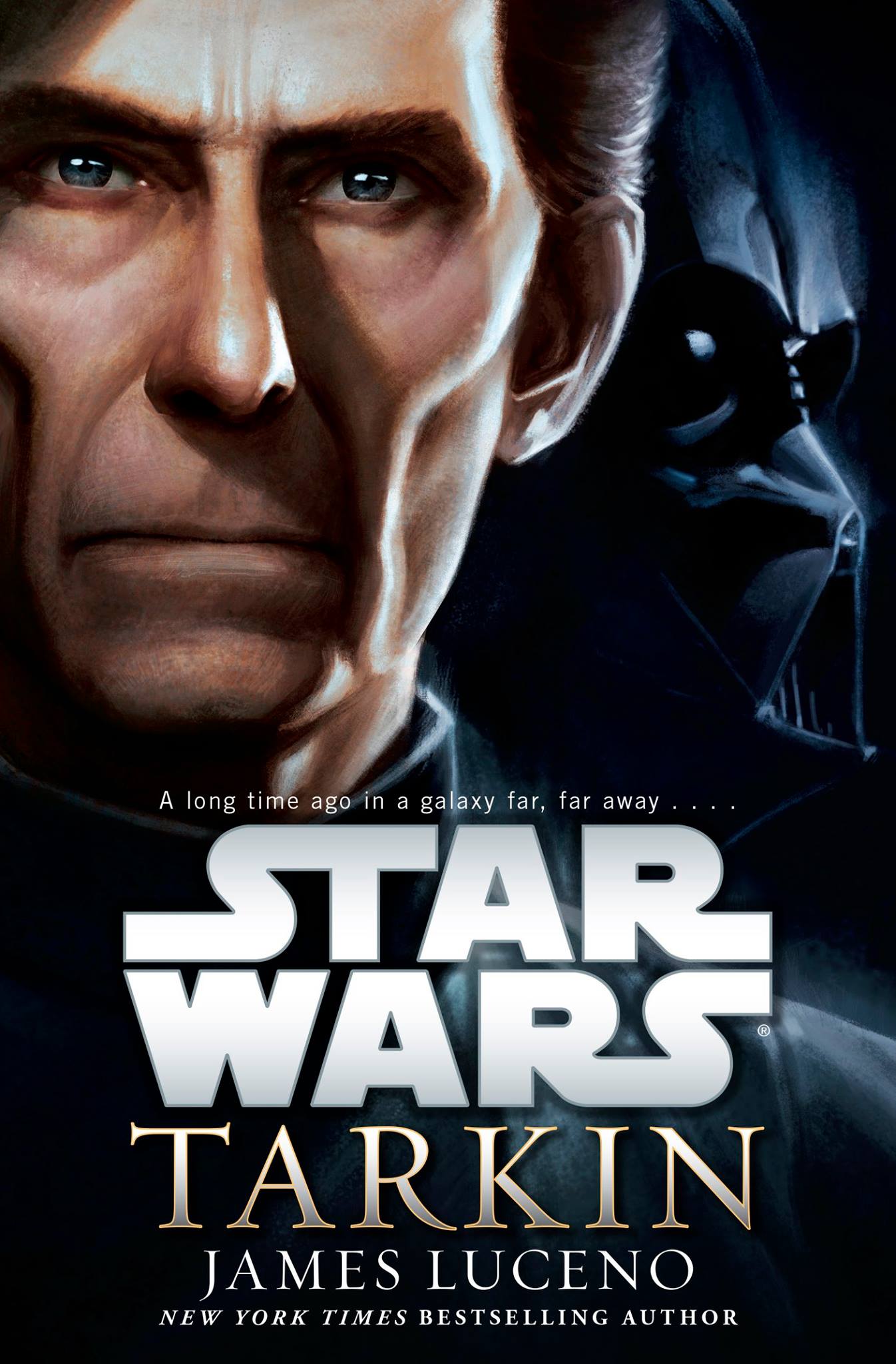

Revelations 22:1-21/ Tarkin by James Luceno

Belonging!

Five standard years have passed since Darth Sidious proclaimed himself galactic Emperor. The brutal Clone Wars are a memory, and the Emperor's apprentice, Darth Vader, has succeeded in hunting down most of the Jedi who survived Order 66. On Coruscant a servile Senate applauds the Emperor's every decree, and the populations of the Core Worlds bask in a sense of renewed prosperity.

In the Outer Rim, meanwhile, the myriad species of former Separatist worlds find themselves no better off than they were before the civil war. Stripped of weaponry and resources, they have been left to fend for themselves in an Empire that has largely turned its back on them.

Where resentment has boiled over into acts of sedition, the Empire has been quick to mete out punishment. But as confident as he is in his own and Vader's dark side powers, the Emperor understands that only a supreme military, overseen by a commander with the will to be as merciless as he is, can secure an Empire that will endure for a thousand generations...

Revelations

Hark! The end of days is nigh! An Eden free of the sins of serpents and men awaits those who accept the Lord their Savior.

In this final address, Jesus urges all to follow him beyond life and to bring everyone who will listen along with them. In the end of days, there will be solace in the unity of acceptance.

But, the very last utterance gives pause to many. Not all who listen feel as though they will come to belong in the arms Jesus has opened wide...

_____________________________________________________________________________

As a Jew, belonging is an integral part of my existence. For thousands of years, my people have struggled with belonging. Should we treat belonging as an exclusive status that only includes our fellow Jews? Or, do we treat belonging as bringing ourselves to belong amongst our non-Jewish neighbors in spite of our vast differences? Our history has and continues to experiment with both options to varying degrees of success on both sides. This week, as part of my efforts to expand my analyses of holy texts, I branched out to the Christian Bible and the New Testament.

Even the mere opening of the Book of Revelations to attempt to deeply understand it as it pertains to belonging made me uneasy. As many similarities as exist between Judaism and Christianity, there are dozens and dozens of Jewish laws and principles intentionally nullified by the New Testament. My greatest concern was how I could possibly speak truth on any subject to anything I may read that is in direct contradiction to my Jewish beliefs. I feel I need to walk a fine line between not blasphemously denouncing the New Testament’s sacredness and its explicit religious implications, and treating it as a literature like any other to be observed and interpreted as I see fit. In fact, this is the same struggle I must endure with reading any holy text.

My ultimate conclusion is that I can deny the truth of the New Testament as it pertains to the will of God while still accepting that there are truths to be found within the text. Essentially, as I analyze the texts, I will neither impose my understanding of God’s will on the God of this Bible, nor will I make comment on my personal disagreement with the assessment of the will of God made by the texts in a way that is demeaning to the sacred text itself or any who believe in its truth. Just as I have done all along with the analyses of Torah, I will continue to strive not to dictate what the truth of a text is, but offer possible interpretations on possible truths. And as always, no interpretations of any text should ever be regarded as my true and sole opinions, as not only are my opinions ever evolving, but I often offer interpretations that may not be my go-to interpretations, but are interpretations that I can derive meaning from and accept as possible interpretations within at the least, the context of the given discussion. Ultimately I want to stay true to my own belongings, as well establish a space where I feel anybody can belong.

Wilhuff Tarkin was a high ranking official in the Galactic Empire, and a close advisor and even once friend of Emperor Palpatine. His position as Grand Moff made him an oversector governor within the sprawling and intentionally convoluted bureaucracy. These were specially appointed positions created by the emperor himself to allow for a consolidation of power to a single individual across numerous galactic sectors, in this case, the entirety of the Outer Rim. Before Tarkin was a Grand Moff, he was a child growing up on a largely untamed planet called Eriadu. The Tarkin family was one, of if not the most prominent families on the entire planet and they had a particular trial they imposed on their young men that oozes with insight into the notion of belonging.

The Carrion Plateau was a vast, untamed wilderness on Eriadu where a young Wilhuff would be tested to verify his belonging to the Tarkin name. Should he succeed in surviving the Carrion and eventually ascending its most traitorous landscape the Spike unscathed, he would be hailed as a full-fledged man. Should he fail, he would die one of endless possibly gruesome deaths. His entire sense of, and actual ability to achieve belonging hinges on this primal expedition. Regardless of Tarkin’s personal retrospective appreciation for the conscious and unconscious development he endured at the Carrion, how the experience was designed was precisely the reason he made the particular gains he did.

Revelation 20:18 reads, “I warn everyone who hears the words of the prophecy of this scroll: If anyone adds anything to them, God will add to that person the plagues described in this scroll.” My first gut reaction was to be appalled. Not because this is not something I am unused to reading in the Torah or Jewish texts, because it is absolutely not. Rather, I was in awe simply at the implications of how I first read the sentence. At first, I took it literally. I understood it to say that all of the analysis that I do of sacred texts is unholy, because I am adding words to the text that never belonged there to begin with. I struggled with how to even begin to wiggle my way out of such an explicit demand without offending the sacredness of the text and without blatant, albeit layered hypocrisy. Hypocrisy in my willingness to add my own two-cents to the text of my own faith that maintains the same dogma as this passage, when I am entirely paralyzed by the thought of going against a text I have already long concluded as bearing no truth as to the will of God. Were this interpretation ultimately the intended meaning in the text, I would accept it in full, as I promised earlier is how I would treat sacred texts. Yet I know that there has to be something more that I have not yet grasped.

I was troubled even further by this passage’s implications for belonging. In social sciences, we believe there are four categories of goods: excludable, non-excludable, rivalrous, and non-rivalrous. The difference between excludable and non-excludable is whether or not somebody has to pay a price or have a particular belonging to benefit from that good. The difference between rivalrous and non-rivalrous is whether there is a limited. The below picture should give a good sense of how these categories combine to explain different kinds of belonging.

In some ways, my belonging to the Jewish people is something I have no control over. I was born into it and thus it is so. Yet also as a free thinking adult, it is entirely within my power to shed my belonging to Judaism and choose a belonging in Christianity. These cleavages of belonging straddle excludable and non-excludable types of goods, depending on which way I choose to think about it, but for the sake of my argument, I am going to lean more strongly towards the former assumption about belonging and consider religion excludable. Tarkin’s trials at the Carrion Plateau also constitute an excludable good because only those with the Tarkin name are even eligible for the challenge. Tarkin learns his well when he asks why his family’s servant does not go to the Carrion and even his kind mother is abashed by the suggestion and responds question who serves whom in that household.

My initial interpretation of this verse from Revelations is a rivalrous good. There is a set quantity of interpretations acceptable (one) and if I do not have that one interpretation, I will not have access to the belonging that comes with it. Tarkin’s trials at the Carrion Plateau would belong in the category of non-rivalrous. There is no finite number of Tarkins that can pass the test or specific means by which his success might be constrained.

If the Bible under my brash interpretation is an excludable and rivalrous good, then it is the complete antithesis of a public good, something that is free to anybody to access and use, no matter how many other people are using it and at no cost. i would hope that that is what any sacred text is. Free and unlimited in its number of possibly correct interpretations. And finally, upon continuously rereading the passage, I understood how I could belong in spite of it all. The text is not asking me not to add my own two-cents or interpretations. It is telling me not to speak anything from the text that is untrue. The next line, verse 19, reads, “And if anyone takes words away from this scroll of prophecy, God will take away from that person any share in the tree of life and in the Holy City, which are described in this scroll.” The text is not asking me not to make interpretations, not acting rivalrously. It is simply providing instructions on how to really engage with sacred texts, whether they are my own or not. To keep texts sacred in spite of my disbelief in their interpretation of the will of God, I have to be certain to stay true to what a believer would consider to be the intention of the text, but am more than free to set my own interpretations within that space. I can essentially belong without belonging.

As for Tarkin’s belonging, sometimes club goods can be valuable. The excludability requires a price, a serious effort to be paid that shaped Tarkin into who he was. Who Tarkin was certainly was a villain, but the kind of belonging he had serves a valuable lesson that not all belongings should be public goods. I Tarkin did not train at the Carrion Plateau, he may never have survived on Eriadu, and he certainly would not have found the great success he did. Some belonging simply should be earned. Just not all belonging. Others deserve to be free of costs, prior and post utilization, and usable by any who so wishes.

Next time:

Today I specifically chose Tarkin as opposed to the new release Catalyst because the events of the newer book may be considered spoilers to many (myself included) for the upcoming film. It was also one of the first New Canon books released, and I want to write in a relatively chronological order of release. In continuation of preparation for Rogue One, this Sunday's post will be a reading of this week's Torah portion, Tol'dot (Gen. 25:19-28:9) and Episode III: Revenge of the Sith through the theme of "family." Family will be a prominant theme in the new film, as it has always been in Star Wars. Rogue One is chronologically set between Episodes III and IV, the later of which I will return to next Sunday as the last film before the new release. It is also the first Star Wars feature film to not revolve around the Skywalker family.

The Tuesday and Thursday posts for next week are still to be determined, but will definitely continue with the first story arc of The Clone Wars and part two of Tarkin.